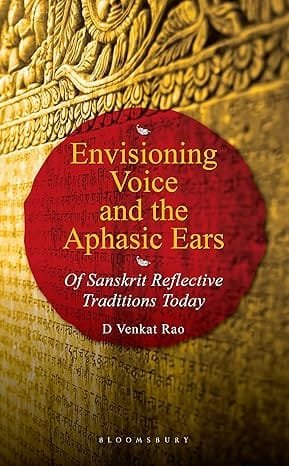

This is a conversation between Prof. D Venkat Rao and Halley Kalyan on Prof.Rao’s recent book ‘Envisioning Voice and the Aphasic Ears: Of Sanskrit Reflective Traditions Today’ (2025)

What follows is a Q&A discussion on some of the critical themes touched upon in his recent book ‘Envisioning Voice and the Aphasic Ears: Of Sanskrit Reflective Traditions Today’ (2025)’

On the relationship between Sanskrit and other ‘Indian’ languages

[Halley Kalyan / @halleyji on X – HK] You mention the following in your book:

Sanskrit fecundated other ‘Indian’ languages (pg xiii)

The reflective strength of many languages inside and beyond ‘India’ was spurred and enhanced by the Sanskrit language. Indian languages draw on the resources of Sanskrit to formulate their own reflective articulations. From the beginning of their interface with Sanskrit, a whole range of languages of different regions brought forth cultural compositions in the languages of the regions and in Sanskrit over millennia (pg xiii).

Elsewhere in the book you write – Bhasha-s gained vitality but flourished independently – through this interface – as vibrant, reflective, creative formations. Today it is impossible to purge any of the bhasha-s of their reflective lexical receptions of Sanskrit.

You mention Sanskrit may have cultivated a mode of being indifferent to ‘foreign’ languages even as they were hospitable to Sanskrit. It seems to have been open to be translated into other languages but rarely indulged in translation of ‘the other’.

How is the relationship between both constituents to be understood in the context of this ‘fecundating’ (fertilising/making fruitful) and indifferent process? Is this always a one-way street?

[Prof D Venkat Rao – VR]

Inquiring into the extended spread of Sanskrit one notices a very consistent tendency: Sanskrit does not seem to seek anything (language and reflection-wise) directly from any of the cultures it interfaced with. But it lends itself to reception by any culture that is open to it. Sustaining such a consistent mode of being can happen only when the resources internal to the culture (that is Sanskrit) have cultivated a certain kind of reflective-performative integrity and vitality that lets it live on without appropriations from others.

Yet, it must be pointed out that Sanskrit prevailed amidst other languages across its spread. Those who unfolded and were made by Sanskrit traditions were not unaware of other languages (Prakrits, Apabhramsha, Paishachi and the bhasha-s of the common ear). Many of them worked with these other languages too in most learned ways (Anandavardhana, Rajasekhara, Nannaya and others). Fecundation of these other languages occurred through such processes of immersive work from the latter. Let’s remember that the early renderings of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata into bhasha-s could not have been done without learning Sanskrit.

But it is difficult to find any reflective impact of the non-Sanskrit languages on Sanskrit in any significant way. As pointed out earlier this could be due to the cultivated integrity of Sanskrit. But it could also be due to two other factors: (i) the unavailability of such reflective integrity among these other languages before the interface with Sanskrit and (ii) even if such a reflective impulse could be seen, Sanskrit would remain indifferent to it until the former is articulated in the idiom of Sanskrit. This happened only with Bauddha and (to a lesser extent) Jaina traditions. The debates and contestations with these latter traditions in Sanskrit remain unparalleled in the context any other language (say the Greek, Latin or Hebrew and Persian or Arabic).

Is it a one-way street? Yes and no. The answer cannot be in black and white terms. If only Huen-Tsang had rendered Confucius or Lao-Tze into Sanskrit and brought it to the notice of his teacher Shilabhadra, perhaps one could have noticed another interesting intellectual opening. One would assume a similar response with the pre- or post-Hellenistic Greeks as well. Megasthenes never learnt Sanskrit despite several years of his stay in Pataliputra. Yet many Sanskrit scholars learnt other languages and rendered Sanskrit learning into foreign languages. Kumarajiva was the first one from Tarim Basin to render Buddhist work from Sanskrit into Chinese (4th-5th centuries). Similar instances can be seen in the Ashokan period in the context of Buddhism across Central Asia.

[HK] You acknowledge that criticism (from western scholarship) exists that Sanskrit is xenophobic, ethnocentric, incurious and a closed tradition (Pg 17). Has Sanskrit transformed itself with these interfaces with other languages and traditions? If not, doesn’t that make some part of the criticism valid to some extent?

[VR] Given my earlier response, it is difficult to see how interfaces (say with Chinese, Persian and Arabic and later European) with the foreign have impacted Sanskrit. I doubt if the reflective integrity of Sanskrit has suffered in any significant ways with its exposure to the foreign. However, as you can, it is possible to see some impact – only in the context of those who learnt Sanskrit and interfaced with the foreign and worked in the foreign languages – it is in their works in foreign languages such changes can, perhaps be noticed. This is blatantly evident in the case of those who teach Sanskrit in/through other languages today (but even such an impact is conspicuous in its absence in the interface between Sanskrit-Buddhism and either Gandharan or Chinese/East Asian encounters).

What is at stake in all this is that Sanskrit seems to respond to reflective modes of being only when they are articulated in the idiom of Sanskrit. It remains indifferent to any kind of attack or praise launched in non-Sanskrit idiom/language. The modern maligning of Sanskrit in European languages betrays insensitivity toward the question of the deep relation between the idiom and reflective modes of being that Sanskrit kindles and nurtures. Without the necessary attentiveness to this relationship, one can hastily repeat the superficial proclamations of Europe.

Sanskrit as the basis of ‘thinking’ in general: Violence of European path vs Sanskrit’s historical spread and experience of living with the foreign

[HK] You write the following:

Envisioning Voice moves on an accessible intuition: Given the longevity and extraordinary spread of Sanskrit (without a proper name, origin, nation, soil, etc.) across most of (Central-South-Southeast) Asia and Europe, shouldn’t it be possible to explore this reflective language as the basis of ‘thinking’ in general? The necessity of such a risky attempt is obvious: today, thinking in general (in all the domains – basically all concepts we work with and the institutions we sustain) is still determined by the European cultural-intellectual heritage. Major European thinkers proclaim even today that there is no alternative to European conceptions of language, art, reason, justice, politics, philosophy, etc. Such an endeavour, to rethink the possibility of a reflective source heterogeneous to that of Europe, will have immense consequences for reconceiving coexistence in a shared universe today (Pg 16).

(This work) affirms the possibility of coexistence and cohabitation without the threat of genocidal violence which European history embodies so blatantly (pg 18).

Sanskrit as the basis of ‘thinking’ is a very powerful thought. However, there are some ideologues who bat for their own mother tongue free of the influence of Sanskrit and English (Europe) both. They see Sanskrit’s influence also as a form of colonization. How do we understand this?

[VR] Nowhere in the extended existence of Sanskrit or other Indian languages do we come across such vociferous assertions about language and identity before their exposure to Europe. The ideology of the mother-tongue is a European legacy (a sort of Rousseauism). Sanskrit was neither a mother-tongue nor father-tongue. No one could own it. So should be the case with other languages as well. However, one can understand such assertions. Modern geo-political violence (demarcating lands and people, displacing, erasing and inciting amnesia with regard to cultures and communities) impels the victims to hang on to the threads that are invested with identity – whether these threads are from an intractable legacy or expediently woven, they are invoked to serve the struggle for recognition and survival. Such identitarian assertions, however, may not contribute to the impulse that enabled the flourishing of such cultures and cultural formations over extended periods.

[HK] Deep down south there is a lot of politicization around Sanskrit for this reason. It is seen as a threat that may erase another language. But history proves otherwise as you mention. Sanskrit traditions never had the genocidal impulse. Sanskrit never sought to homogenize. Some elaboration is needed on the possibilities of co-existence and how other languages can retain their uniqueness despite the hospitable interface with Sanskrit or lack thereof.

[VR] As is well-known, this delusive rage to purify language/culture in our contexts is of a very recent origin – second half of nineteenth century. Despite the unimpugnable fact that it is not possible to purge Sanskrit idiom from most of the major Indian languages, there are assertions of such aspirations. Such assertions may yield some domestic returns to gain expedient powers but cannot respond to the inheritances that nurture those languages. Tamil is an eloquent instance of such operations. It seems to me that the two-millennia of Sanskrit-Tamil intimate cohabitation – and the distinctive modes of being and reflective forms that such intimacy has nurtured cannot be disavowed beyond a point. Such disavowals can manifest only as denegations of what one says and what one does.

[HK] What makes Sanskrit special compared to other ‘Indian’ languages? Is it unique because it has something that other languages do not carry or cannot offer?

[VR] The uniqueness of Sanskrit, if one were to speak about it, is its ineradicable impulse to live on as it enlivens others. Even today most of the major languages and cultures continue to be enlivened without being dominated by Sanskrit.

Western experience of language and experience of Sanskrit

[HK] You contrast the imperial, national, homogenizing, babelian, religious, translational – Western experience of language with Sanskrit that affirms without force or penal authority.

What explains this difference in Sanskrit viz., Western experience of language. Is this because Sanskrit didn’t aim to replace any language? Sanskrit never aspired to be the ‘national’ language or the language of/for all?

[VR] Sanskrit has never been a language of conversion. Similarly, the Greeks did not impose their language in the post-Alexandrian territories. Only Latin as it became invasive, especially after it turned religious (that is Christian), began to impose itself on other cultures. Latin became not just the language of culture and that of the intellectual, but essentially the language of the church. Whereas Sanskrit had neither a church nor a religion nor did it have a kingdom to exemplify in the name of its language. Living on with others seems to have been a distinctive feature of Sanskrit’s longevity and vitality. It evinced no drive to be universal nor any urge to impose itself as a lingua franca. Only those who are the heirs of such cultural aspirations have, in the recent times, characterized Sanskrit as “cosmopolitan” and “political”. Sanskrit nurtured no polis nor was it fattened by any polis.

[HK] How can one contrast the European experience of language (Latin, English, French etc.,) with Sanskrit’s relationship with itself and its others – how it cohabited in spaces where it was forever exposed to the foreign? Is there any other language in the history of world languages with a comparable spread or influence and with this kind of characteristic?

[VR] As pointed out earlier, by the end of the first millennium of the common ear all the major European languages were subsumed into Christianity. The traces of their earlier (‘pagan’) moorings were either suppressed, erased or sublated into Christian religion. Despite the obsessive claim of Heidegger of a direct lineage between the Greek and German language (considered the only languages conducive to philosophical reflection), it is not possible to dissociate the German language from the impact of Christian (also Judeo-Christian) heritage. Each of these languages with a deeply shared religious heritage evinced intolerance with regard to other European languages to a certain extent and non-European languages wholly. It is difficult to think of any other language (other than Latin – with a heterogeneous trajectory) that is comparable to Sanskrit’s ways of living on.

Sanskrit and India

[HK] You write:

One must learn to understand that ‘India’ and Sanskrit cannot be easily conflated. The term India has had no presence at all in the extended Sanskrit traditions. It has not yet acquired any conceptual salience even now. The national-territorial conception of India might appear to be much larger than what is projected as ethnically oriented Sanskrit. To be sure, the conception of India today contains religious communities like Muslims and Christians (and other minority groups) and a preposterously totalized but wholly untotalizable ‘community’ called the Hindus. The latter is an expedient projection based on the Semitic conception of community as formed by a common religion. Despite its apparently more encompassing reach across all these communities, the expedient idea of ‘India’ can barely be said to provide any shared patterns of reflection or experience across the heterogeneously proliferated clusters of people: ‘India’ is yet to provide any shared understanding of being together with others who are unlike each other (Pg 322).

[HK] How do we look at the construct of nation-state and territorial allegiance in this context? We cannot divorce away from it as Indians but at the same time we cannot also succumb to semitising impulses alluded to above or broadly succumbing to the euro-colonial impulses. However, we are a part of a nation whether we like it or not. We need to answer questions around national identity, national culture, national policy on something like education etc. How do we deal with this situation?

[VR] Very true. It will be a dangerous delusion to disavow what is called India today. It is important to remember that such a geopolitical categorization (which has everywhere begun to unleash its violent impulse) itself is an expedient emergence of an inordinately violent history – the history of European religious wars (which were said to have eliminated 5 to 8 million people). The categorization is the result of “peace” agreements and introduction of “tolerance” as a virtue. The post-Westphalian territorial divisions (with language-identities), the sublimation of the concept of “sovereignty” and the colossal impact of these machinations on the geo-physical and biocultural existence of the planet is yet to be unraveled from outside this overpowering invasive framework.

It seems to me that cultural flows (I would prefer the phrase performative modes of reflective being) and territorial borders cannot be made isomorphic in relation. The European framework hinted at here works with such isomorphisms. “India” is the result of such straight-jacket enframing. Yet it cannot be dispensed with for some sentimental reasons. What I learn from the inquiry that moves me is that such categorization cannot be allowed to exhaust the deeper currents and intimations which it tries to encompass.

The skirmishes that we see today among the educated in India is an eloquent symptom of the failure to see this distinction between the framing and the enframed. Sanskrit, and the ethos and the idiom it honed over millennia, I learn, cannot be regimented through such an enframing. Let’s remember that both the cherished terms the Hindu and India are the labels forged by foreigners and are imposed on an inexhaustible horizon that shaped the resilient formations of liveable learning. Yet working from within the constraints of these categories, it should be possible to explore ways and modes which move beyond the constricting territorial limits.

In such a context, Sanskrit throws open yet another possibility of living on in the world with others. I try to trace these intimations in the work that I have been doing. But a lot more work of reflective practice is required to be done to sustain this unraveling of European framework. Cultures that nurtured themselves outside the fold of Europe for extended periods, when they sense their rhizomic sources outside the territoriality of Europe, perhaps, can contribute to this unraveling. In such an immense task Sanskrit, it seems to me, provides enlivening resources of inquiry.

[HK] Would you distinguish between India and Bharata? (Bharatadesha, Bharatavarsha, Bharatakhanda and other such terms that may be older than India and indeed used in Sanskrit traditions and Indian languages)

[VR] Surely a relevant and expected question. It is possible to understand the search for such a nomenclature that has some salience to counter the foreign impositions. But such a gesture may be merely nominal unless one begins to understand its imports. Such terms to a very large extent referred to a royal genealogy, markers of (imaginary or real) geophysical spaces, locations, ritual domains; Bharatavarsha also refers to the entirety of the manifest visible formation prone to appearance and disappearance; and Bharati referred to the entirety of the sonic horizon. In other words, it referred to the totality of the visible and audible world that emerges and dissolves. It must be added that the term Bharata is also used to refer to those who enhanced the ethos emerging from the Vedic learning. (cf. Bharati Nirukti).

Yet all these apparently dispersed references have never been brought together for a configuration of what Sanskrit unfolded. We must remember that in all these references, the Bauddha and Jaina are conspicuous in their absence. In other words, Sanskrit is much more expansive and welcoming and one must see to it that what is configured by the Bharata connotations must not confine the reach of Sanskrit to some circumscribed spaces, modes and practices. In the absence of such efforts, even the remarkable reach of the Bharata connotations may be in danger of being reduced to the modern geo-territorial-political conception of India. As can be seen, the prevailing conception of India wholly falls short of the range and reach of Sanskrit and Bharata. The latter are our resources for an unforeseen reflection that may help us to unravel the invasive categorizations which determine and regulate our existence today.

[HK] You write:

The pathos-ridden rhetoric of ‘India’ is a testimony to the continuing intellectual destitution, and it aggravates the asymmetry between Sanskrit and ‘India’. In such a scenario of confounded confusion, the enduring experience of Sanskrit across foreigners, across uncharted territories, and the lasting hospitality its intimations received among heterogeneous assemblages of biocultural formations (from Gandhara to Jakarta), should help one in grappling with the most radical ethical-political question of living on with the unlikely others – those who are not like us. Sanskrit seems to beckon one to move on from the path paved by the fatal embrace of the Semitic. It has already hinted this primal sense when it forged and differentiated the vaak as moving between sva-artha and para-artha. That precious hint cannot be delimited by the specificity of time and space though it can communicate to specific times, spaces, and formations. The hint does not sublimate an epistemic venture but it can warm modes of being and forms of reflection as one moves on with heterogeneous others. One beckons such a future anterior of Sanskrit in the darkening shadows of our intellectual destitution: itisamsarateetisamskrutam (Pg 323)

[HK] Influences and intimations of Sanskrit traditions can operate even on someone who cannot read, write or speak Sanskrit? How do you explain the centrality of Sanskrit traditions to Indian culture even if there aren’t as many speakers and content creators in Sanskrit? Does that matter? There is also the (Semitic?) impulse to make ‘Sanskrit the language of (daily) communication for all’ and make sure ‘Sanskrit reaches every single household’ so on. How do we avoid that pitfall as a people? That doesn’t seem desirable and that doesn’t seem to have a precedent either?

[VR] I am convinced that inquiry into Sanskrit can no longer be (it has never been) a defensive and apologetic gesture championed by some belated reformist spirit. Sanskrit cannot be conscripted for proselytization. A language, any language, lives on only when it is put to work by creative and reflective users of that language and it lends itself to a variety of uses. Language replenishes and rejuvenates itself through such immersive acts. However, only when the language is seen to enable such uses does that language invite its reception and response from its users. Today we see an abyssal gap between the immense capability of the Sanskrit language (in its intractable and inexhaustible weaves over millennia), its reflective traditions and the languages of education that prevail in every field. Our modern “enabling” education has systematically occluded our access to the creative-reflective field and horizon of Sanskrit. We are programmed to transport/translate Sanskrit, without sensing what it is capable of offering, into the dominant categories of thought that have been implanted with force and persuasion. Today we no longer need the presence of a foreigner to regulate this violence. We are the vectors through which such violence gets perpetuated.

The critical impulse of Sanskrit is not confined only to Sanskrit language. It has already been actively received and honed in the warm abodes of other languages (all the major bhasha-s of India and beyond). We need to learn to sense that impulse from within the contexts in which we get programmed – the academia and the university. Nearly eight generations have been exposed to this programming. There are no shortcuts to the task of unlearning. Programmes of populism and propaganda are detrimental to this immense task. Only those who sense the beckoning of the creative and reflective intimations, whose reflections are performative, can respond to this task in silence and slow time with patience and perseverance. Such a task cannot be measured by quantity and number.

Zealotry hijacking traditions of Sanskrit

[HK] You write:

Danger of zealotry hijacking the traditions of Sanskrit in the name of a territory, soil, blood and nation. Sanskrit opened up the possibility of modes of being and forms reflection without any dogmatic investment in the idea of the proper or property (ownership, nationality and possession) (pg 17)

This is a recurring theme throughout the book. Continued emphasis on this concept that Sanskrit isn’t limited or bound by any of the above – territory, soil etc. You refer to descriptors like timeless, nameless (anaami) and so on. How do we explain the unique flourishing of Sanskrit and Sanskrit influenced languages and traditions for the longest times on this land (i.e. what is today called ‘India’) as compared to elsewhere where Sanskrit travelled? Doesn’t ‘India’ have the highest density of Sanskritic traditions, many languages that were hospitable to Sanskrit and many Jati cultures that interfaced with Sanskrit for the longest time? Isn’t this relation between Sanskrit and ‘India’ special? Doesn’t that matter? Does it mean that even if it matters, it matters for ‘India’ but not for Sanskrit? Is that the import here of trying to not explicitly associate Sanskrit with territory or soil or blood or nation?

[VR] You are very right in emphasizing the long flourishing life of Sanskrit in what is today called India. Also, it is true that most of the reflective traditions of Sanskrit have flowered in this (today’s) geopolitical nation-state territory. But as is well-known these territorial categories are of very modern nature. Sanskrit’s movement cannot be measured or confined to these boundaries.

Take a look at the contours of its traversals – un-programmed and without a set pattern. It drifted into the (extended) Punjab via the Gandhara and beyond. From there it moved on further toward the east to various locations up to Magadha horizontally, and to Kashmir and beyond the Vindhyas vertically. In my work, I sketch these passages as forming cultural constellations (Gandhara, Brahmaputra, Madhyadesha, Dakshinapatha, Sangama etc.,). Wherever it traveled it touched the places and people, and brought forth countless cultural clusters. Such internally differentiated cultural clusters are made possible by what can be described as the bio-cultural formations and their distinctive cultural forms. Such forms and formations in turn assemble the cultural constellations. These cultural formations are at once centripetal and centrifugal in their manifestations and dispersals.

Now, these constellational contours did not seal Sanskrit’s borders in any way. It moved from Sangama (Tamil country and Keralam) further beyond toward the East and the West. Ashokan emissaries carried it in certain inscriptional forms to the Hellenistic Egypt (Alexandria). Indonesia, China, Myanmar, Cambodia, Thailand and other cultures are deeply touched by Sanskrit in different ways. The indelible marks of this touch are tangibly available in language, gesture and artifacts across all these cultures. Sanskrit flourished in Cambodia for over a millennium. Once again it is the Semitic invasions that covered up these throbbing veins of Sanskrit in most of these eastern locations.

In the Indian context, it seems to me that, when exposed to a hostile situation, it is the very traversals of Sanskrit that enabled its extended life. Secondly, Sanskrit found hospitality in the interstices of most of the Indian bhasha-s, which kept it alive in the reflective currents of these languages. It seems to me that the charita (mode of being – also that which moves –chara) of Sanskrit’s vibrancy and dynamic drift across the cultural constellations into other locations is yet to be figured out. I am afraid the charita of Sanskrit cannot be elicited from only historical and philological searches. This is the immense task that awaits the reflective creative beings across all these locations. Therefore, I find it difficult to conflate Sanskrit with “India”. Sanskrit never sought to survive on advertisements and commercials (let’s recall that Sanskrit was neither the language of soldiers nor of tradesmen – army and economy).

IKS / Indian Knowledge Systems

[HK] In the concluding portions of the book you also write about learning to unlearn the heritage of the university (the paradharma) and caution that an anxiety or zeal ridden drive to forge a methodology for what is hastily called these days the Indian Knowledge Systems will only aggravate our intellectual destitution unless we first face an already belated task of configuring and unraveling the paradharma (Pg 322)

Elaborate on this in the context of current upsurge of IKS activity all over academia and otherwise.

[VR] I cannot help saying that the urge for forging a or the methodology for/from the “Indian knowledge systems” is blatantly a questionable colonial legacy. It is difficult to see any consolidation of such a methodology in the extended reflective traditions of Sanskrit. The recent urge for such a method, it seems to me, foregrounds and elevates a particular darshana (Nyaya) and advances it as something that works for the entirety of Sanskrit reflective traditions.

I suspect that even this elevation itself is the result of the attention this darshana received in the early phase of post-independence period – the attention that came from a deeply fraught intellectual (mathematical/logical/positivist) wave that shaped the US philosophical inquiry. My suspicion is that this zeal for the method retards further the necessary inquiries that must emerge from the Sanskrit traditions. It seems like we are still being compelled defensively to answer the questions that the West has framed for us. Of late we only seem to answer in shrill and aggressive tones.

Important thinkers like J.N. Mohanty and J.L. Mehta (in different ways) have sensed the ways in which we are plunged further into the thickened shadows of Western reflective legacy. I seriously doubt that any university (including those that uphold Sanskrit learning) presently is in a situation to dispel these shadows effectively. This is not a criticism of the work done over generations by many concerned people. It is to point out the tenacity of a certain kind of structural violence that established our modern educational system – a system that perpetuates patterned asymmetry between Sanskrit traditions and the European disciplinary systems of thought.

Regarding the putative ‘Indian Knowledge Systems’ now on the ascendant. I must place on record that this initiative has spurred new enthusiasms and elicited new energies in the moribund academic scenario in the Indian context in the last few years. IKS sparked a certain kind of confidence and it seems now to enable certain assertions. Above all, it seems to inculcate fresh interest in the heritage of Sanskrit. Most of these initiatives are sustained by some kind of financial support. At the same time the incubation and advancement of these initiatives is largely driven by technology and management gurus of the academy. The larger university structure and the expanded college systems are yet to be moved by the new enthusiasm. The reasons for both these factors must receive attention but the attention seems to lie elsewhere.

The college and the university structures are philosophical conceptions even though they are largely dominated by the sciences. In other words, the modern university is itself constitutively riven by the division between the humanities and the sciences where the latter dominates. This divide has a very ancient source in the European heritage but the modern university aggravates this division. In the Indian context, this deeper nexus between the philosophical and discursive-institutional division has barely received attention. Given that the institutional base and the ‘pioneering’ efforts of IKS enthusiasts rests mostly with the management-tech folk, these efforts are barely sensitive to the complex genealogy of the university and the division of its disciplines of thought.

Consequently, IKS initiatives are bound to be determined by the structural division that the university embodies. No wonder why the spirit of IKS is time and again asserted as “scientific”. Such assertions take recourse to a certain kind of ‘monumentalist history’ – of inventorying and projecting the work of a cultural past as essentially scientific. Consequently, the humanities side of the university gets homogenized as the Western and it either gets ignored or demonized.

No wonder every IKS initiative by default as it were foregrounds its essential scientific nature. No wonder, the tech-management lingo of LLMs, startups, codes, the angelic AI, and collaborations, companies, has begun to pervade the IKS from its very start. Such initiatives have begun to birth the new avatar of the profession which can be called: cyberneutics – coding and decoding interpretative profession. The cyberneutic professional is likely to champion the Sanskrit reflective traditions henceforth through the ventures of the IKS.

It seems to me that intellectual destitution prevails when we are not able to ask our questions and pursue our inquiries and above all – without being able to risk configuring who we are. The blinding enthusiasm of IKS has barely taken up the difficult task of formulating its questions: What questions should we be asking in today’s context and what inquiries should we be initiating? Knowledge of Sanskrit, though certainly important, alone is not of help in formulating these questions. One has to expose oneself to the dominating and violent intellectual heritage of the West without caricaturing the latter into a straw figure. The IKS venture simply embraces, without inquiry, what has been projected as the greatest achievement of the West: science and technology.

Lest what is being said should be misunderstood, let me clarify: this is not a plea for the redressal of the structure of the university in favour of the humanities (though the NEP glibly proclaims its aim of advancing the “liberal arts” university – a derivative and unexamined credo). The skirmish between science and the humanities is a legacy of European intellectual heritage (with ancient roots in the structure of trivium and quadrivium). This skirmish gets fought in the modern university on the rules of the game determined by the technologized sciences.

Should we be heirs of this battle? Why is it that the extended Sanskrit reflective traditions did not breed such divisive disciplines of thought (the sciences and the humanities)? How did these performative reflective traditions grapple with the domains of learning (the number, nature and the ends of vidya-s and kala-s)? What are the intimations one receives from the non-privileging of the concept of the human or the mathematical in these traditions? It seems to me that we need to calm down (and not race with the West for the latest) and reflect on the directional hints that Sanskrit bequeathed us over millennia in changing contexts.

It seems to me that IKS – in its laudable aim of connecting the younger generations to the learning of the past – must provide some space for more enduring inquiries – inquiries that move beyond the cynical short-term returns (the much touted term – prayojana). One hopes that the new enthusiasms and energies tolerate such inquiries of silence and slow-time. IKS, I am convinced, inaugurated a deepening and widening churn and churning releases disturbance. One will have to wait and see what the churn offers – be it nectar and/or nescience.

Islamic epoch and European colonial epoch:

[HK]: You write:

Were Sanskrit literary and musical, let alone reflective, traditions altered in any significant way with the presence of Persian and Arabic-Islamic sources? (pg xiii)

Languages and cultures of ‘India’ began to get systematically disoriented with the implantation of European educational models spread across discourses, languages and institutions. In a word, cultural transmission was disrupted and de-formed through the paradigmatic cultural model which Europe advanced normatively (such disruption can be traced back to the Islamic epoch as well). (pg xv)

Fundamentally how do we need to differentiate between the impact of Islamic epoch and the European one (Christianity and Secularised Christianity)? Both are Semitic at their core. But the impact on ‘India’ and Sanskritic traditions in particular has been very different in both epochs. Some of these effects are still continuing even today. Why did these two epochs operate differently?

[VR] Yes, they – Islam and Christianity – are the warring (Biblical) siblings (along with Jews) of the Western heritage. Although there is plenty of work that shows the difference between these traditions, the way they unfolded in/from the Indian context still requires inquiry. One significant difference here is that Islam in its spread did not invest in taking over the entire educational organization. The guru-sishya pedagogical structure was not entirely and systemically disrupted. Raghunatha Shiromani in the 16th century (when Hussain Shah had already rooted himself in Bengal) could come back from Mithila and establish his tol to train students.

Europe ripped apart precisely this extraordinary pedagogical model with ancient roots. The most devastating blow of Europe was in displacing and disregarding the traditions of inquiring learning and inquiring teaching – traditions that were sustained in countless places across villages and cities. The singular aim of European rule was to alter the mind of the native – epistemic alteration. The consequence of this is to undermine the modes of being and forms of learning on the one hand and stigmatization of the nurturers of such learning traditions.

Vidyas and kalas in the entirety of Sanskrit (and Bhasha) traditions have always been sustained by divergent biocultural formations. Teaching and learning was never monopolized by one centralized authority (there is no church here). Europe arrogated to itself the power to teach from a podium as it were. The consequences of this expropriation of learning-teaching-inquiry model are ubiquitous in our disoriented educational ventures today.

The stark irony of this situation is that Europe itself shaped its own educational institutions from the medieval times through the educational models of the Buddhist viharas (which were nurtured by Sanskrit traditions) via Islam. Islamic madrasas were based on Buddhist viharas from the 9th century onwards. These in turn inspired the European colleges from 12th century onwards (and the classical universities of Oxford, Cambridge, Paris etc.,) drew on this legacy. Similar development can be seen in the Islamic schools in Indonesia which appropriated Buddhist learning centres and modeled their pesantrens – sort of madrasas. Once again, the ways and forms in which Sanskrit moved (the charita of Sanskrit) is an immense task awaiting further exploration. Although, Islam and Christianity derive from the Biblical roots, their work and response to Sanskrit has been different in the domain of institutional formations.

Sarva DarshanaSamgraha (SDS) – Mleccha Purvapaksha

[HK] You write:

it is impossible to trace any sense of the presence of Islamic cultural or religious trait in the reflective portrayal that the SDS elaborates. The absence is understandable. The Samskrutavaangmaya systemically remains in-different to the ‘foreign’ presence, even when it circulates and proliferates among the divergent ‘foreign’s. The reflective integrity of the vaangmaya does not seem to spur any anxiety or zealotry to incorporate the foreign into its expansive presence. On the contrary, it is the Semitic foreign (most pronouncedly the Christian) which races purposively to expropriate Samskruta and fix it in a frame. This is a kind of expropriation where the appropriated has no say at all, for the language of adjudication remains that of the invasive expropriator. In the interface between the Semitic and the pagan, the latter remains a muted being. The question of justice in such a context is adjudicated by the Semitic (Christian) judge and jury (Pg 266)

..violent asymmetric relationship between the Semitic and the pagan. (Pg 266)

Is this indifference to the other by design or by choice or due to lack of any threat perception of expropriation or even erasure in the hands of the foreign religion?

[VR] In a way we have already touched upon this point. It is a cultivated indifference. It seems to me that Sanskrit traditions are deeply sensitive to the ways and modes of being as/and reflection. In other words, they are not given to simple instrumental use of the languages of speech and gesture. The ways in which the body is put to work is of utmost importance here. This sensitivity to what is said and the way it is articulated cannot be separated (though they are separable) in the horizon of Sanskrit. Therefore, unless the ‘foreigner’ learns to articulate himself in the idiom of Sanskrit, Sanskrit will not respond. Secondly, there is also a certain kind of indifference toward even such foreign learners.

The word mlechcha hints at that: those whose speech is not clear and whose utterances are asaadhu. Many Sanskrit savants distanced themselves from mlechcha-s. It is said that in the 16th century a pandit of Kashi refused to enter the palace of Akbar when the latter wanted to discuss something about some Purana. He remained outside the palace wall, was lifted on a plank to be visible to Akbar. The pandit spoke to another Brahmin (possibly in Sanskrit) and the latter passed it on to someone who knew Persian and Hindi. The conversation was never direct. This can be seen in the entire ‘translation’ venture of the Mughal court: summaries of itihasa, purana themes rendered into Persian. I doubt if there was any threat or fear in this indifference. It is a cultivated sense of the work of the body (speech, gesture, reflection).

[HK] The lack of a substantial purvapaksha of Semitic religions SDS style has been puzzling many for years. You refer to the conspicuous absence of a Semitic Purvapaksha elsewhere in the book. This indifference doesn’t seem to have helped in retaining the spread and vitality of Samskrita Vangmaya.

[VR] As I said it is a cultivated indifference, though it was never, in my view, explicitly thematized or discussed with some agenda. Sanskrit always grappled with purvapaksha – real or imagined. It is a significant aspect of what I call mnemocultures – cultures that live on with embodied and enacted memories: situationally responding to interlocutors – who spur further response from the defender of a position (siddhanti). In such a scenario the absence of a Semitic purvapaksha is conspicuous. This absence did not come in the way of the proliferation and enduring extensions of Sanskrit. It always worked amidst the foreign.

[HK]Significant semitization seems to have happened over the past millennium . Particularly so in the post- colonial epoch? Although to their credit the Sanskrit and Sanskrit intimated traditions have survived better compared to the experience of pagan others elsewhere.

How should Sanskrit traditions react to the current predicament? Indifference to the other doesn’t seem to be an option anymore?

[VR] You are quite right about the waning of other pagan cultures. Some tend to argue that the Greek culture disappeared with the onslaught of the (‘barbaric’) Latin and later the Semitic cultures because the former was insufficiently consolidated by that time. I doubt this is the case with Sanskrit, though I am reluctant to refer to any consolidation of Sanskrit to confront an invasion any time. Sanskrit never espoused itself as an identity marker. Sanskrit simply moved on toward more hospitable receptions. Unlike the Greeks, Sanskrit (let’s recall that there is no equivalents to the term Greeks – referring to a more or less unified group – in the context of Sanskrit. It sounds absurd to say: Sanskrits (to refer to any unified community) did not move with a sword or a horse nor with a scepter like Christianity). Yet, it proliferated incomparably.

The second part of your question must be answered with care and concern. Sanskrit’s “indifference” is used to malign it in the modern period. As pointed out earlier, it is during this period Sanskrit began to be deprived of its most critical resource: its students. Further the learning inquiries of Sanskrit, without the necessary engagement began to be enframed within the ‘novel’ methods of probing forged in the context of the study of the Bible. Historical, philological and interpretive forces of Europe, largely driven and managed by scholars from deeply religious background began to determine the meaning and essence of Sanskrit as a priestly culture. Such onslaughts are unintelligible to Sanskrit and they imposed themselves largely in an alien language shaped by religion. With waning patronage, Sanskrit continued its work from its essentially decentralized nodes from different locations.

There is an abyssal gap between Sanskrit and the educational system implanted by Europe with force and violence. It is wholly unfair to expect Sanskrit to directly respond to the intellectual heritage of the West. It seems to me that one possible opening could be, an opening without guaranty, is to strive and undo the violence from within the modern educational institutions. This would require a pertinent awareness of the intellectual trajectory of Europe and its strategies, methods and structures. Such an awareness can be, in principle, gained in the modern institutions. One’s attempt to know Europe, however, is not with the view to translate or transform Sanskrit into European frames, to turn Sanskrit into European thought. On the contrary knowing Europe is essentially is to inquire into the nature and reach of European inquiry: how does Europe think and why does it do so?

If, knowing Europe is the first step, the second step is to strive to inquire into the performative reflective trajectory that Sanskrit unfolded over millennia. I tried to sketch these double moves in the book in a little more detail. We must prepare ourselves to assess the reach of the European trajectory from the background of the intimations of learning inquiries that Sanskrit opened up. This is the immense task I referred to earlier.

[HK] You write about paaschatya purvapaksha – “Today, the form, structure and method of every academic programme – even those of Sanskrit and other Indian languages – are entirely derived from the determinations of the ideals of paradharma- that of entirely unexamined paaschatya purvapaksha” (Pg 316)

“Configuration of the Mleccha Purvapaksha will have to be risked” (Pg 318)

You also refer to apraachya darshana and Praachya-Apraachyamatavedana/darshana (Inquiry into the east and non-east reflective positions) (Pg 321)

Please elaborate on how this Purvapaksha needs to come forth. Who are the actors that need to come together for this and how do we go about this – Academia (Policy makers, Student, Faculty and Community etc).

[VR] I have partly responded to this question above. Who has to take up the immense task? Well, all those who sense the unease with the prevailing institutions and what they offer. I am convinced that these institutions have “enabled” us to aggravate the disjuncture between what we are made to think, in the ways we think and the lively ciphers of experience that still glimmer in our modes of being: the festivals, rituals, the touch of the seasons and the breezes, aromas, and tastes these seasons surround us with (think of Shravana and the festive atmosphere all over). Most importantly and enduringly, the ways in which these experiences are enlivened in the language, literature and performative forms of every region by every cultural formation.

As a university teacher, I tend to think that my task is to share with students this unease and work along with them to think together – even if we part ways in thinking differently. We must learn to see the classroom as a space for learning-inquiry and inquiring-teaching. The Upanishads always enacted such a process of learning. In the academic context (university is just one institutional structure but it is very crucial), all the teachers, students, and administrators must learn to respond to the disjuncture and strive to pave way for other modes of being and thinking. It is possible to outline this task in a scalable manner – but this inquiring teaching must begin from the university. It is the university/academia that prepares other role players (be they teachers, bankers, politicians, strategists, soldiers, judges, entrepreneurs etc.).

[HK] You mention the intellectual destitution of generations of students and teachers (and the emerging policy makers) in this context (Pg 316). Can you give some specific examples where policy makers falter due to the lack of appreciation for all this?

[VR] Let me confine myself to the university. Teachers and administrators are the policy makers of the curriculum of the university. Ever since the university was implanted (in the second half of the 19th century), it instituted an asymmetric structure of teaching and learning. European knowledge gets privileged and the receiving student gets silenced as an inheritor of a civilization with extended longevity. In my view none of the educational policies (including NEP) showed the ways of displacing such a structure, though everyone is eloquent about the need for decolonization.

Yes, it is very true that one cannot wish the structure away. It is not some bureaucratic decision to replace one structure with another (as the putative IKS seems to suggest). It changes little. In the perpetuation of this asymmetric structure generations of teachers, administrators, students are involved and we are complicit in its continuation. There is no shortcut to redress this situation. Only through the process of deeper engagement with these traditions (Sanskrit/Indian and European), without alibi, and through novel ways and modes of continuous inquiry in different domains, one can think of transforming the violently hierarchic structure of education that continues to determine our thinking today. Envisioning Voice and the Aphasic Ears sketches these issues and suggests the possible ways of grappling with them.

An elaborate and expanded video version of this conversation is hosted on Atharva Forum’s Youtube channel as ‘Sanskrit Reflective Traditions and the Call of the Mlechha Purvapaksha’

No Comment! Be the first one.